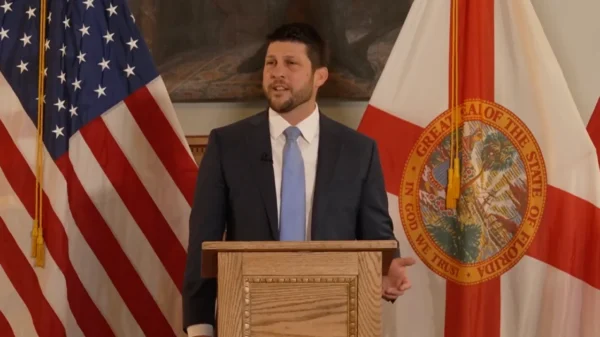

Last week, U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla. wrote to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) ahead workshop titled, “Non-Competes in the Workplace: Examining Antitrust and Consumer Protection Issues.”

In the letter, Rubio urged the commissioners to “bear in mind the harm that noncompete agreements cause to lower-wage working Americans.”

Earlier this Congress, Rubio introduced his “Freedom to Compete Act,” legislation that would protect entry-level, low-wage workers from non-compete agreements which limit their future employment opportunities and restrict their ability to negotiate higher wages and benefits. At a U.S. Senate Small Business and Entrepreneurship Committee hearing late last year, Keith Bollinger, a textile worker, testified how non-competes harmed his career prospects. Rubio chairs the committee.

The full text of the letter is below.

Dear Commissioners:

I am pleased that the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is turning its attention to the question of noncompete agreements and their effects on American workers. In advance of your planned workshop, Non-Competes in the Workplace: Examining Antitrust and Consumer Protection Issues, the FTC issued a notice with several questions of interest to the Commission, the first of which was: “What impact do non-compete clauses have on labor market participants?” I urge you to give due consideration to the straightforward answer to that question: the proliferation of noncompete agreements has caused great harm to American workers and their families.

American economic success has always relied on the power of free competition. Noncompete agreements directly restrict free competition in the labor market, prohibiting employees’ freedom to join or start a competitor after they depart their current employer. This practice has traditionally been justified as a means of protecting a business’s trade secrets or unique investment in an employee. This logic has generally meant that such agreements are aimed at senior-level employees. But noncompetes have become widespread across many sectors and wage levels. Approximately one in every five American workers is bound by a noncompete agreement, with an estimated forty percent of all American workers having been bound by a noncompete agreement at some point in time. Noncompetes bind fourteen percent of workers who earn less than $40,000 a year, and fifteen percent of workers without a four-year college degree are beholden to a noncompete agreement.

Numerous studies indicate that the proliferation of noncompete agreements depresses wages for working Americans. When an American worker’s ability to seek or create a better opportunity elsewhere is deliberately restricted, their wages are inevitably decreased, not only by limiting future opportunities for better pay, but by giving current employers tremendous leverage over current pay negotiations. This wage depression is measurable even in the absence of noncompetes being actively enforced and is all the more egregious when noncompetes are enforced against such workers. Enforcement action against textile workers, security guards, hairstylists, sandwich makers, construction workers, and many others has badly, and sometimes permanently, disrupted and damaged the personal, family, and financial lives of working Americans. This is both transparently unjust, and inherently anti-competitive and economically counterproductive. This trend is made all the more egregious by the fact that in many cases, noncompete agreements are not freely negotiated in the first place, often having been presented to employees as a condition of employment only after the start of such employment. These facts are well-documented, and were the subject of a Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship hearing I chaired on November 14, 2019.

Numerous states have restricted the use of noncompetes for workers below a given income threshold, to protect working families from the damaging effects of noncompete agreements. Studies indicate that average wages increase meaningfully in states that have restricted the use of noncompete agreements. I have put forward a legislative proposal to restrict the use of noncompete agreements for workers who are not exempt from the Fair Labor Standard Act’s wage and overtime rules. Others in the United States Senate have also forwarded proposals seeking to restrict the use of noncompetes. Support continues to build with the reality that working Americans have the right to compete in the market.

As the Commission investigates the question of noncompete agreements, and contemplates potential action, I urge you to bear in mind the harm that noncompete agreements cause to lower-wage working Americans.