This week, the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence convened an open hearing for Ambassador William Burns, the nominee to be the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

The open hearing was a WebEx Hybrid and was followed by a closed hearing immediately following the open session.

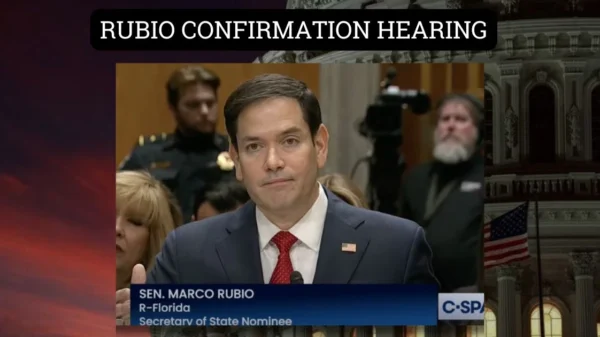

U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., is the vice-chairman of the committee. His opening remarks as prepared can be found below.

Ambassador Burns, I join the Chairman in congratulating you and your family on your nomination, and welcoming you to the Committee today.

As you know, the role of the CIA Director is without parallel in American government. If confirmed, you will sit at the nexus of the Agency’s intelligence collection, analysis, covert action, counterintelligence, and liaison relationships with foreign intelligence services. Responsibility for any one of those mission sets would be an enormous undertaking, let alone all of them.

The CIA Director is responsible for both managing the CIA officers of today — and cultivating tomorrow’s CIA workforce. This entails ensuring that the specialized skills and expertise needed to solve today’s unique intelligence challenges are resident at CIA, but also looking ahead a decade and thinking about what that next critical skill set is going to be. I’d appreciate your insights into how this might best be accomplished, from the vantage of the Agency’s Director.

On the subject of workforce management, I want to mention that the Committee is extremely invested in ensuring that CIA officers injured in the field are afforded access to the healthcare and benefits that they need — particularly when it comes to injury claims consistent with the symptoms of traumatic brain injury.

If confirmed, I ask for your commitment to work with the Committee to find the appropriate legislative and policy changes to ensure that CIA’s commitment to the health and care of its officers is never in doubt, and that we are applying the necessary resources to determine who and what is behind the “directed energy” or “diplomatic attacks” that personnel from several agencies of government have suffered.

Let me be clear, the U.S. Government must forcefully respond to any actor responsible for injuring Americans serving our nation abroad.

Today, the United States faces a litany of diverse national security challenges that includes a military and economic near-peer competitor in China, long-standing hostility from authoritarian regimes in Russia, Iran, and North Korea, a global pandemic moving into Year Two, violent extremism, and state and non-state cyber actors who infiltrate and plunder government and private sector computer networks alike with what seems like impunity.

But no challenge we face rivals the holistic threat posed by China, and more specifically the Chinese Communist Party. As we look to shift our emphasis from counterterrorism to threats from ascendant authoritarian nation states, the threat from China is the most existential to the United States.

We cannot just be orderly caretakers of America’s decline, as so many of our adversaries wish. We must confront and frustrate the ambitions of the Chinese Communist Party to upend norms, amend boundaries, and replace the liberal democratic order with their bleak view of order. This will involve strengthening and expanding alliances but also stiffening our resolve.

This is not the same system of crises that past CIA leaders were called upon to defend against. The threats today are sudden, unpredictable — and with greater frequency — occurring in a gray space that embraces the objectives of conflict, without quite crossing the line into outright warfare.

What is plain to me, is that the world has changed how it chooses to engage the United States. What I would like to hear from you today, is whether the CIA needs to change how it engages the world. I hope that over the course of our open and closed sessions today, you’ll take the opportunity to explain not only your understanding of the CIA’s unique role in American government, but your vision for how that role needs to evolve in the coming years so that the Agency is positioned to defend against those emerging national security threats that have not yet materialized.

There is no disputing the speed and unrivaled capability that the CIA can bring to bear in responding to a fully realized national security threat. You only need to look at the early days of our involvement in Afghanistan after September 11th to see that.

What I’m driving at, however, is an intelligence apparatus oriented toward the technological advances and global inter-connectivity that will underwrite the next generation of threats to this nation’s security.

Artificial intelligence, advanced data analytics, biotechnology, disinformation, deep fakes, and social network manipulation: America’s adversaries have used, and will use, these instruments and other new technologies to close the capabilities gap that has advantaged us as a nation for decades.

The refashioning of the national security threat picture by these technological and methodological advances calls into question whether the traditional constructs of espionage need to be refashioned along with it.

I would welcome your thoughts on this subject, both today and going forward, and add that this is exactly the kind of undertaking that is benefitted by CIA’s working in partnership with the Committee.

It is my hope – and expectation – that you will look at this Committee as a partner for the CIA’s work as our nation’s first line of defense. The relationship between CIA and this Committee is premised on oversight, but it is most effective and most constructive when we are candid, open, and talking to one another.

Ambassador Burns, as the Chairman indicated, you have a lengthy and distinguished career of service to the nation. I thank you for your willingness to resume that service, and I look forward to your testimony.Thank you, Mr. Chairman.