A new group called Floridians for Water Quality Protection has launched with plans to focus on protecting Florida’s water quality.

The new group wants to shine some light on is the myriad of local fertilizer ordinances throughout the state.

“The state of Florida essentially has 410 cities with their own rules and regulations or nothing at all when it comes to local fertilizer ordinances,” said Eric Brown, the director of agronomy of Massey Services. “This has essentially created a conflicting – and sometimes very confusing – patchwork of local fertilizer ordinances that are not based on science and are doing more harm than good when it comes to our water quality.”

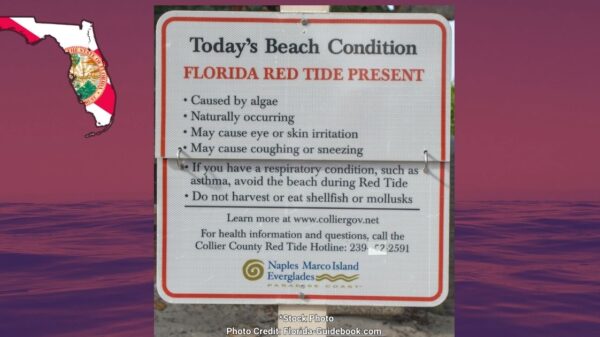

The group noted in 2018, the increase in algae blooms and red tides showed the continuing failure of local ordinances to impact these issues.

“Some of these local ordinances go against proven science and independent, third-party data, as well as Florida statute,” Floridians for Water Quality Protection pointed out.

Mac Carraway, the executive director of the Environmental Research and Education Foundation, said that a county in Florida may have completely different rules than a city located in it. He said local controls have failed to meaningfully address this issue.

“However well-intended, the ordinances simply ignore the established peer-reviewed findings that healthy lawns and landscapes contribute little if anything to runoff,” said Carraway.

“Some believe that many local ordinances appear to have been designed by people who don’t care about protecting Florida’s water quality,” according to Stuart Cohen, the president of Environmental and Turf Services.

Cohen, who used to work with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) added that this has become a serious matter.

“Healthy lawns and landscapes act as some of the most efficient and effective filters on the planet and support the well-being of the environment and I’m concerned that the scientific support for these ordinances has been manipulated,” said Cohen.

Cohen also said that supporters of a local ordinance have relied on graphs of nitrogen and phosphorus in various water bodies purporting to depict an improvement in water quality to get their proposal enacted. However, after the ordinance was passed, Cohen said that it was revealed that the data had been “cherry-picked” and the trends had started before the ordinance had passed.

State environmental protection agencies and the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences have opposed fertilizer ordinances and have stood against bans that are not based on science. They insist these types of ordinances and bans do not address the root causes of nutrient loading, including septic tanks and failed sanitary and stormwater systems.

“This conflicting patchwork of ordinances is also just a distraction from the acknowledged contributions of septic tanks and failed sanitary and stormwater systems,” said Carraway.

Carraway said while many areas throughout the state are hurting their waterways and wildlife with conflicting and harmful fertilizer ordinances, there are some municipalities in Florida that have passed consistent ordinances that work with the natural environment and are appropriate. Carraway noted the Indian River Lagoon mostly has one consistent rule across a single body of water, adding that this has led to improved water quality in the area.

Supporters of water quality protection note that 30 states have developed one state standard or preemption on fertilizer and said that Florida needs to join them.

“These conflicting fertilizer ordinances that are not based on science, some of which have been in place for ten years, are inherently misleading and have given trusting Floridians false hope, and have accomplished nothing,” said Carraway.

According to the new group’s website, Floridians for Water Quality Protection “is made up of scientists and academics, local businesses, green industry professionals and community leaders, who are all concerned about protecting Florida’s water quality, now and for future generations.”

Reach Ed Dean at ed.dean@floridadaily.com.