The polling industry has faced criticism for underestimating Republicans through several cycles. Pollster Nate Cohn recently wrote that the 2022 polls could do it again. These continued misjudgments can undermine public faith in how the media covers elections. Worse still, they can affect the result of close races.

Many 2020 Senate polls underestimated Republicans. In Maine, all polls taken during 2020 showed Republican Sen. Susan Collins losing. The last poll before the election had Collins down by six points; she won by 8.6 points. Similarly, the last poll for Montana’s Senate race showed Republican Sen. Steve Daines losing by one point. Daines won by 10 points. South Carolina faced a similar problem, and Iowa, though not as dramatically, also dealt with inaccurate polling. Finally, polls in North Carolina showed Republican Thom Tillis losing. Tillis won.

Bad polls can affect a race in various ways. One of the most important concerns campaign spending. In 2020, GOP donors spent millions in races propping up incumbents who they thought were in trouble.

Conversely, donors may have abandoned candidates who they believed were too far behind. Many wrote off Collins. In Arizona, polls during the final week showed Republican incumbent Sen. Martha McSally down by as much as 10 points, but she lost by only about two. A Fox News poll from two months before the election had McSally down by 17 points. When that poll was released, much of the media counted McSally out. While it’s possible that the polls tightened, it seems more likely that she was never really down by 17 points.

In Michigan, polls showed businessman and Republican Senate candidate John James down by an average of five points. James ultimately lost by less than two points. The results were so close that it took a few days to call the election.

Moreover, polls earlier in the 2020 cycle affected media coverage. In Alaska, liberals crowdfunded for Public Policy Polling to conduct a poll of the state’s Senate race. The poll showed the Republican incumbent Dan Sullivan at 39 percent, up only five points over Democrat Al Gross. This led to the viral campaign “don’t sleep on Gross” and millions being spent on the race. Yet Gross lost by more than 12 points and underperformed President Biden in Alaska, which calls into question that early poll.

Voter enthusiasm will differ in a race that is within a point or two versus one that has a five-point spread. New Mexico and Minnesota’s Senate races ended up closer than those in South Carolina, Montana, and Maine, but polling outlets were far less active in New Mexico and Minnesota than in those other states. Had these two states received more polling, their races might have attracted more money and voter enthusiasm.

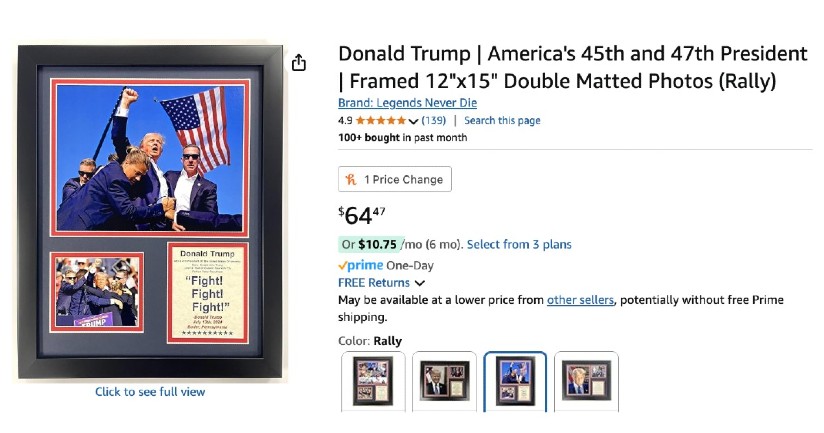

And polling errors are not limited to Senate races. Polls in the last week of 2020 showed Donald Trump losing Wisconsin by as much as 11 points; Trump lost by less than a point. In 2021’s New Jersey gubernatorial election, none of the nonpartisan polls gave the Republican candidate, Jack Ciattarelli, a chance at winning, yet the race was decided by just three points.

As Cohn noted, the past might repeat itself. Yet several of the same outlets are making projections for November based on polls with less-than-stellar recent track records. These kinds of mistakes could affect the results this November and further diminish public trust in the organizations that conduct and publish these polls.

Todd Carney is a lawyer and frequent contributor to RealClearPolitics. He earned his juris doctorate from Harvard Law School. This article was originally published by RealClearPublicAffairs and made available via RealClearWire.