Guest Op-Ed by Derrick Max

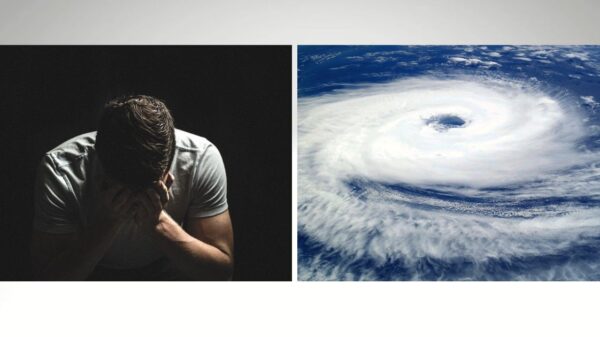

The first hurricane of 2024, Hurricane Beyrl, is now in the books. Beryl reminded us that hurricanes are a powerful force of nature – a force that causes much fear and anxiety. The stronger and more destructive the hurricane, the deeper it becomes ingrained in our collective consciousness. Katrina, Andrew, Sandy, Harvey – hurricane names that will forever be associated with destruction and death.

Sadly, as with most destructive weather events, these events quickly become fodder for climate extremists to tie our fear of these events to “climate change” or more specifically, “man-made climate change.” Beryl is no exception, “Is Hurricane Beryl the sign of another dangerous storm season? Climate change is fueling the frequency and intensity of storms” cried the headline in The Week.

Surprisingly, the actual data rarely matches the headline, a fact that seldom gets coverage in the mainstream media. Even government agencies, according to meteorologist and oceanographer Bob Cohen, often lead with alarming statements about increased weather severity, but the data show a different story. The truth is that the number of hurricanes (remaining offshore and making land) impacting the continental United States hasn’t significantly increased over the past century.

While Atlantic hurricane formation does exhibit a very slight upward trend recently, the records indicate a peak much earlier, as the graph below shows. Sparsely populated areas in the early 20th century might have missed weaker storms, leading to underestimates.

Similarly, the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale used to categorize hurricanes based on sustained wind speed, with higher categories signifying greater destructive potential, also shows a very minimal increase in intensity over the last decade.

More importantly, the causes of the modest increases are more complex than climate change – and there is little to no evidence linking the data to “man-made” climate change. There are cycles in ocean temperatures like El Nino and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) that are not climate change related and can impact hurricane activity. These naturally occurring patterns have an oversized impact on the number of hot days and hurricanes we experience. As can be seen in this University of Arizona chart overlapping AMO phases with hurricane patterns, AMO phases dominate the data.

Distinguishing long-term trends from natural variability requires a robust dataset – which currently does not exist. Reliable hurricane data with consistent recording methods only extends back to the mid-20th century, and the best records came with the satellites. Earlier records may be incomplete or lack crucial details like wind speed, hindering our ability to conclusively identify trends before this period.

While the absolute number of U.S. landfalls might not be skyrocketing as the headlines suggest, several factors heighten the perception of increased hurricane risk which then fuels the climate extremist language. The 24/7 news cycle provides constant updates, amplifying public anxiety. The stronger the storm, the greater the coverage, the greater the sense of heightened danger – the greater the likelihood that it will be falsely attributed to climate change.

As noted above, the psychological impact of past devastating hurricanes lingers long after the storm has passed. Events like Hurricane Katrina in 2005, which caused $65 billion in damages and 1,408 deaths, remain etched in our collective memory, shaping the public perception of hurricane risk even though no hurricane since has caused more than 83 deaths.

Yet no one mentions that hurricane cost impacts are due primarily to population growth and coastal development. As more people reside in hurricane-prone areas, the potential for damage and loss of life rises. A Category 3 hurricane in 1900 striking a sparsely populated coastline would have a vastly different impact compared to one hitting a densely populated city today. Again, this is unrelated to climate change.

The notion that the number of U.S. hurricanes has dramatically increased over the last century doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. Nor does the notion that hurricanes have become more intense. Yet, an increasing number of Americans are willing to risk their and our collective economic vitality on the altar of “carbon zero” policies. These policies significantly increase the cost of doing business, reduce our competitiveness, and risk massive blackouts — all based on false reporting on climate change.

Virginia is currently in the process of re-examining its extreme climate policies as spelled out in the Virginia Clean Economy Act (VCEA). This act is forcing the mothballing of hydrocarbon-based energy production methods before reliable “clean” alternatives are online.

As with the myth of significant global warming and sea rising — hurricane hysteria should be rejected. Policymakers should put energy reliability and economic impact ahead of any measures to reduce the risk of claimed climate impacts which are nothing more than the same storms that have always appeared, at unpredictable times, and thus cannot be prevented by changes in human behavior.

The right approach to hurricanes is to invest in improved infrastructure that can withstand strong winds and storm surges. Coastal communities should invest in seawalls, enhanced draining systems, and strengthen their building and zoning laws. When the warnings do come, people need to take them seriously. Not ironically, these are the types of investments that should be made for most of the risks we face, investments that aren’t being made because we are unwisely investing in wind, solar, and battery technologies that are yet to be proven and will have no impact on hurricane frequency or intensity.

Derrick Max is the President and CEO of the Thomas Jefferson Institute for Public Policy. He can be reached at DMax@thomasjeffersoninst.org.

Anker SOLIX C300 DC Power Bank Station, Outdoor 288Wh Portab...

$189.99 (as of May 20, 2025 16:03 GMT -04:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)EF ECOFLOW Portable Power Station DELTA 2 with Waterproof Ha...

$499.00 (as of May 20, 2025 16:03 GMT -04:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Portable Power Station 300W (Peak 600W), 230.88Wh Solar Gene...

$129.99 (as of May 20, 2025 16:03 GMT -04:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Jackery Explorer 300 Plus Portable Power Station, 288Wh Back...

$219.00 (as of May 20, 2025 16:03 GMT -04:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)MARBERO Portable Power Station 88.8Wh Solar Generator 150W P...

$68.99 (as of May 20, 2025 16:03 GMT -04:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)